The 2013 Boston Marathon and the 2010 BP Oil Spill crises were black swan events that tested the imagination, coordination, capabilities, and management of numerous stakeholders across levels of government (local, state, and federal) and the public and private sectors.

These traumatic outlying events inflicted extraordinary impact and offered retrospective predictability. Every crisis is novel but includes recognizable features that demand agile problem-solving, adaptive leadership and unity of effort. Crisis characteristics include the need for speed, control, and robust stakeholder engagement combined with the effective management of confusion, stress, uncertainty, and immense financial costs. The Boston terrorist attack and the Gulf oil catastrophe share trademark features of a crisis but significantly differed in the ability to achieve the leadership phenomenon known as swarm intelligence, which resulted in lasting and contrasting public perceptions of each mission’s success.

The Boston Marathon bombing response is largely recognized as a case study in effective leadership that produced remarkable results under complex and confusing circumstances. The successful outcome is largely evaluated by the lives saved, the swift capture of the suspects, the high levels of public trust, and an overall sense of resilience in the tragedy’s aftermath. Indeed, Boston is strong.

Researchers from the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative (NPLI) credit the success of the emergency response with the existence of a leadership dynamic that coalesced around a shared desire to accomplish more together rather than achieving separately. The theory known as swarm intelligence is comprised of five principles: 1.) unity of mission; 2.) generosity of spirit; 3.) deference for the responsibility and authority of others; 4.) refraining from credit and hurling blame; and 5.) a foundation of trust and prior relationships.[i]

An established pattern of collaborative stakeholder engagement facilitated an effective response during the immediate incident, the subsequent rolling crisis in Cambridge and Watertown, and post-crisis recovery efforts. The effective response is largely credited to the multi-dimensional preparedness among federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies, participatory public entities, and other response organizations, as well as state and local elected officials.

Preparedness, high levels of coordination, and a unity of effort among participating entities positioned the City of Boston and the Boston Police Department to maintain control and authority throughout the crisis while also influencing the narrative in the face of uncertainty and risk.

The BPD has a long history of institutional and personal relationships with law enforcement counterparts. Local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies have formally collaborated and conducted detailed planning exercises for many years on numerous high-profile, large-crowd events, including the annual July 4th festivities, beloved Marathon Monday, and frequent professional sports events and victory celebrations. The long history of stakeholder partnerships contributed to a cultural mindset of strategic and operational coordination during the crisis.[ii] In fact, the NPLI study showed that leadership coordination strengthened throughout the week and resulted in a “unified cadre of crisis leaders.”

Considered the largest maritime disaster oil spill in American history, the April 2010 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig and its aftermath of economic, environmental, and political fallout offers critical lessons in crisis management and the importance of swarm intelligence, specifically how a crisis unfolds and how it is perceived when unity of effort is elusive.

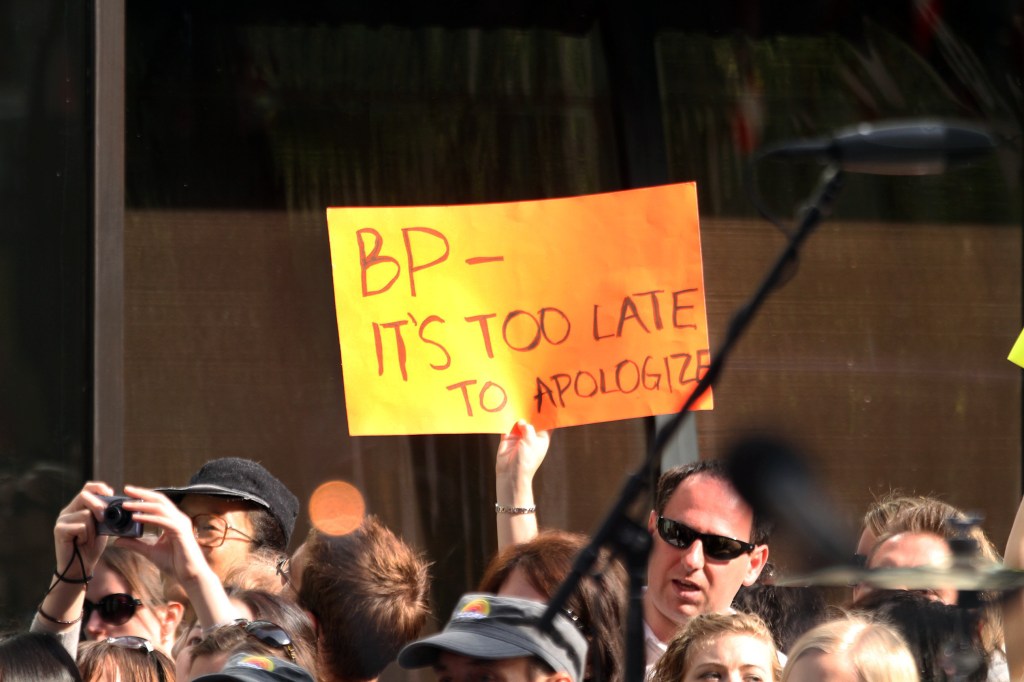

BP Oil’s failure to prepare and build partnerships in advance of the disaster led to a lack of trust and legitimacy with the Gulf communities and levels of government stakeholders. Their failure to immediately acknowledge the gravity of the incident and provide timely and factual situational awareness led to intense blaming and finger-pointing during response and recovery. Insufficient preparation rooted in optimism bias and negative stakeholder relationships intensified anger, political jockeying, and perceptions of crisis responsibility, leading to irreparable reputational harm for BP Oil and an overall negative public perception of crisis management efforts.

The National Incident Command, led by the federal government, was forced to manage the consequences of BP’s deficient preparedness and absent allies. The result was a lack of unity, competing agendas, hurling blame, and low public confidence. Political theater disrupted the operational response, requiring the NIC to strategically engage governors and other elected officials with daily updates. Tensions boiled over between government administrations that were seeking relevance and pressure on BP to stop the problem. A failure to achieve swarm intelligence prolonged the effects of the incident, created a competitive environment among stakeholders, and threatened recovery efforts. The absence of a unified effort manifested in a negative public perception of operational success despite the NIC’s impressive accomplishments regarding harm minimization during the recovery phase.

The Boston Marathon and BP Oil Spill disasters provide key reflections on the importance of the first two stages of crisis management: protection and prevention. Preparedness and stakeholder coalitions facilitate unity of effort and influence the narrative. Perception is reality; therefore, the public’s judgment of operational success is shaped by leadership’s ability to present a narrative that conveys transparency, unity of purpose, and, most importantly, hope. BP’s efforts to minimize damage, shift blame and withhold public information undermined the herculean efforts of the other responding agencies.

Low probability, high-impact events like the marathon and oil spill underscore the value of swarm intelligence and its impact on effective response and perception. Both incidents challenged public and private sector authorities with the need to rapidly identify remedies while simultaneously confronting an existential threat to organizations, stakeholders, and whole systems.

No organization can operate independently of its stakeholders. Strong relationships must be built before disaster strikes. Preparedness includes forging alliances, gaming out a coordinated response, developing a deep understanding of stakeholder roles, understanding the stakeholder impacts and predicting how stakeholders will react when the crisis hits.

Stakeholder alliances may not prevent a black swan event from occurring, but they will determine the success, both real and perceived, of the crisis response.

[i] Leonard Marcus, Ph.D. et al., “CRISIS META-LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM THE BOSTON MARATHON BOMBINGS RESPONSE: THE INGENUITY OF SWARM INTELLIGENCE,” April 2014, https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2443/2016/09/Marathon-Bombing-Leadership-Response-Report.pdf.

[ii] Herman B. “Dutch” Leonard et al., “Why Was Boston Strong?,” April 2014, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/research-initiatives/crisisleadership/files/WhyWasBostonStrong.pdf.

Leave a comment